Worked Example - Horticulture¶

The worked example for the horticulture module demonstrates the integration of xlwings and koala libraries through User Defined Functions (UDFs) designed for a given calculation which may have multiple definitions.

The horticulture module supports the calculation of Growing Degree Days. For those who have not come across this kind of calculation before;

Growing degree days (GDD) is a weather-based indicator for assessing crop development. It is a calculation used by crop producers that is a measure of heat accumulation used to predict plant and pest development rates such as the date that a crop reaches maturity.

The purpose of a growing degree day is essentially irrelevant for the illustration. What is important is there are many ways of calculating a growing degree day, and that the math is usually quite simple. We can see the growing degree days article on Wikipedia defines two different methods of calculating a growing degree day.

and

It is possible to have more than two definitions to calculate a growing degree day, but for this example two is plenty.

In the case of growing degree days, the integration at the center of FlyingKoala provides the ability to use any definition with two variable terms as the formula for a growing degree day.

The User Defined Function signature for a growing degree day:

=DegreeDay(model_name, T_min, T_max)

We can see the signature requires the name of a model and two terms. We will get to the concept of a model in a moment but the two terms are easy to understand as they are expressed in the above formulae. Irrespective of why, the example growing degree days formulae both use two.

The actual Python code behind that UDF;

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

from flyingkoala import flyingkoala as fk

def DegreeDay(model, T_min, T_max):

"""Function for calculating Degree Day"""

inputs_for_DegreeDay = pd.DataFrame({'T_min': np.array([T_min]), 'T_max': np.array([T_max])})

return fk.EvaluateKoalaModel(model.name.name, inputs_for_DegreeDay)

In the above code there is no mention of any mathematical relationship between T_min, T_max or the un-mentioned T_base. So how does the call to the UDF do any calculation? This is where the FlyingKoala ‘magic’ comes in. We need to define the math in an Excel formula.

It’s best if the definitions of terms and equations (/models) are named ranges, sometimes called named cells.

And although you can put these elements anywhere in a workbook, I have found it useful to organize worksheets for things like constants, formulas, raw data and workings.

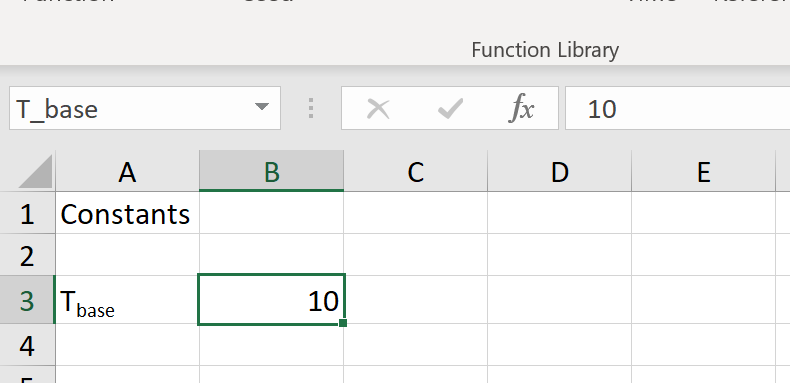

First up define the ‘constant’ terms. Constant is in quotes as these are values which have a typical value, but may change. As the adage goes; ‘this value cannot change because {of a good reason}’ and the moment it’s fixed it has the need to change.

In our case this is the base temperature, \(T_{base}\). Usually 10 Degrees Celsius but doesn’t necessarily need to be.

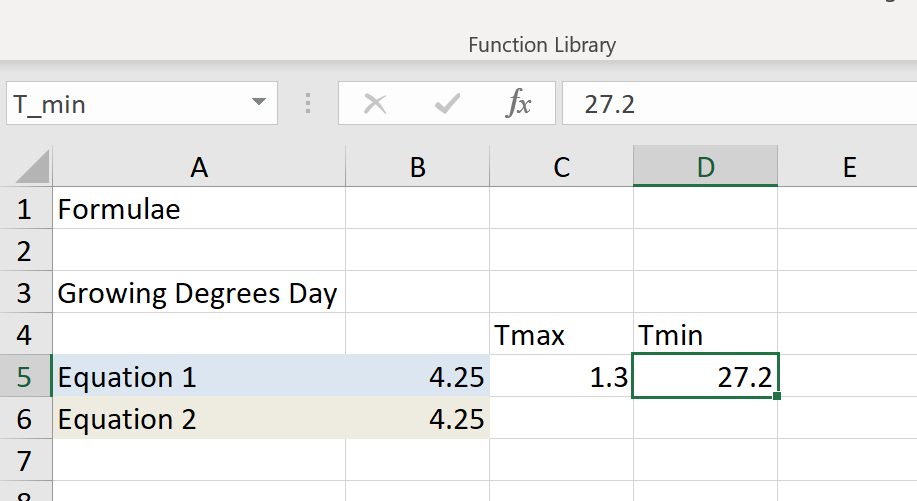

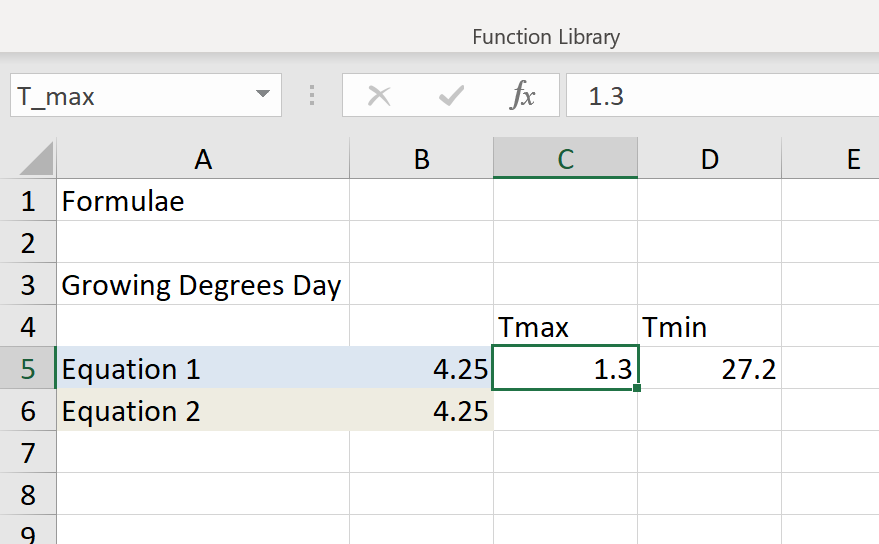

Next up are the equation’s variable terms. These are assured to change.

Minimum temperature for a day, \(T_{min}\)

Maximum temperature for a day, \(T_{max}\)

It can be noted that both growing degree days formulae have the same number of terms. This may not be a coincidence. Much of the time a calculation to a particular end only needs a certain number of terms. In other cases the terms used are the only ones available and so, by implication, the number of them is unlikely to change.

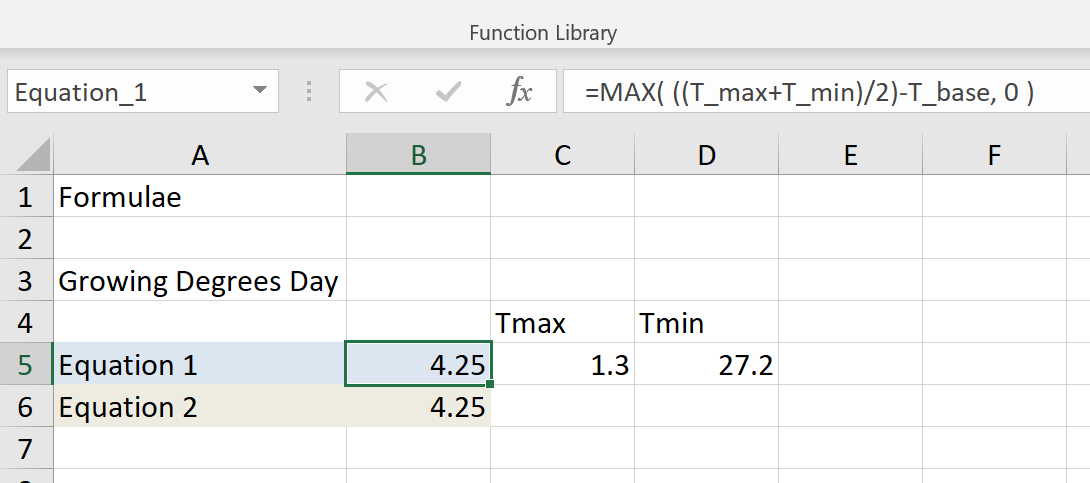

Now that we have named range definitions for each of the terms in the equation, it’s time to define the equations.

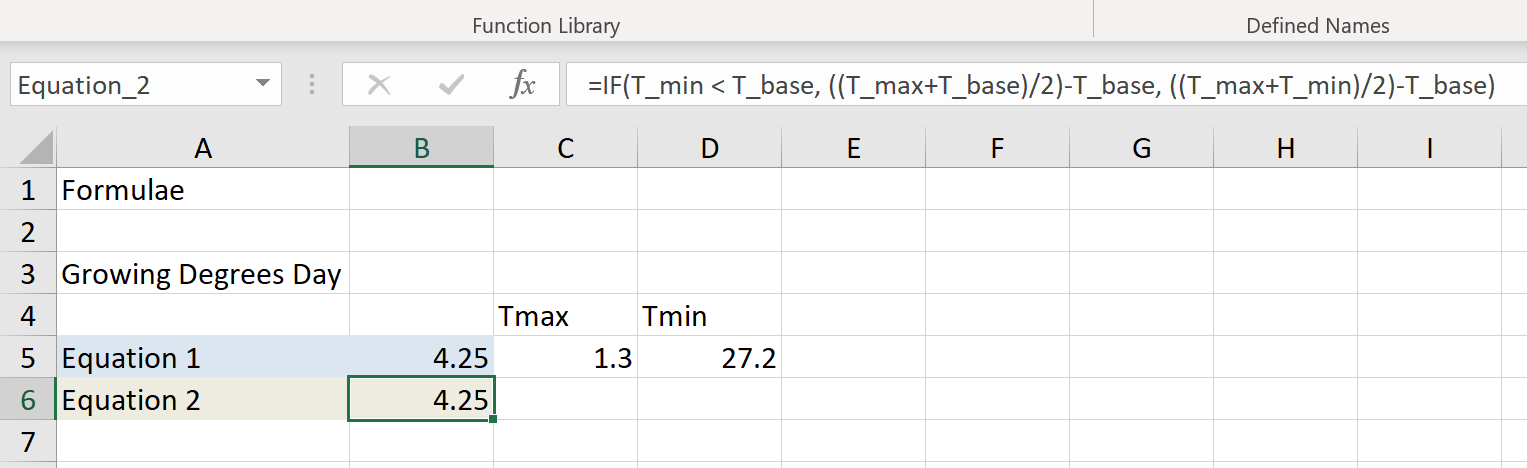

I had no good way of labelling these equations so have simply called them Equation_1 and Equation_2.

This is Equation_1.

And this is Equation_2.

We can see the use of the named ranges for both the constant and variable terms enhances the expression of the formula. Another advantage of setting the formula up this way is that you can put values in to test the formula. It is a little labour intensive, but you can use this to calculate values which check your formula expression.

We are now at the point of using these formulas.

A growing degree day value is not much good on its own as it is the sum of them which becomes useful.

For obvious reasons daily temperature data is most often expressed as a time series. But, there is more than one way to tackle this;

- Fill-down on a formula

- Use a Dynamic Array

For the above reasons,

- DegreeDay() UDFs \(T_{min}\) and \(T_{max}\) require values or cells (returns a single value) and

- DegreeDayDynamicArray() UDFs \(T_{min}\) and \(T_{max}\) are each cell ranges (returns a Dynamic Array).

For the Fill-down approach

=DegreeDay(model_name, T_min, T_max)

can now become something like

=DegreeDay(Equation_1, $B2, $C2)

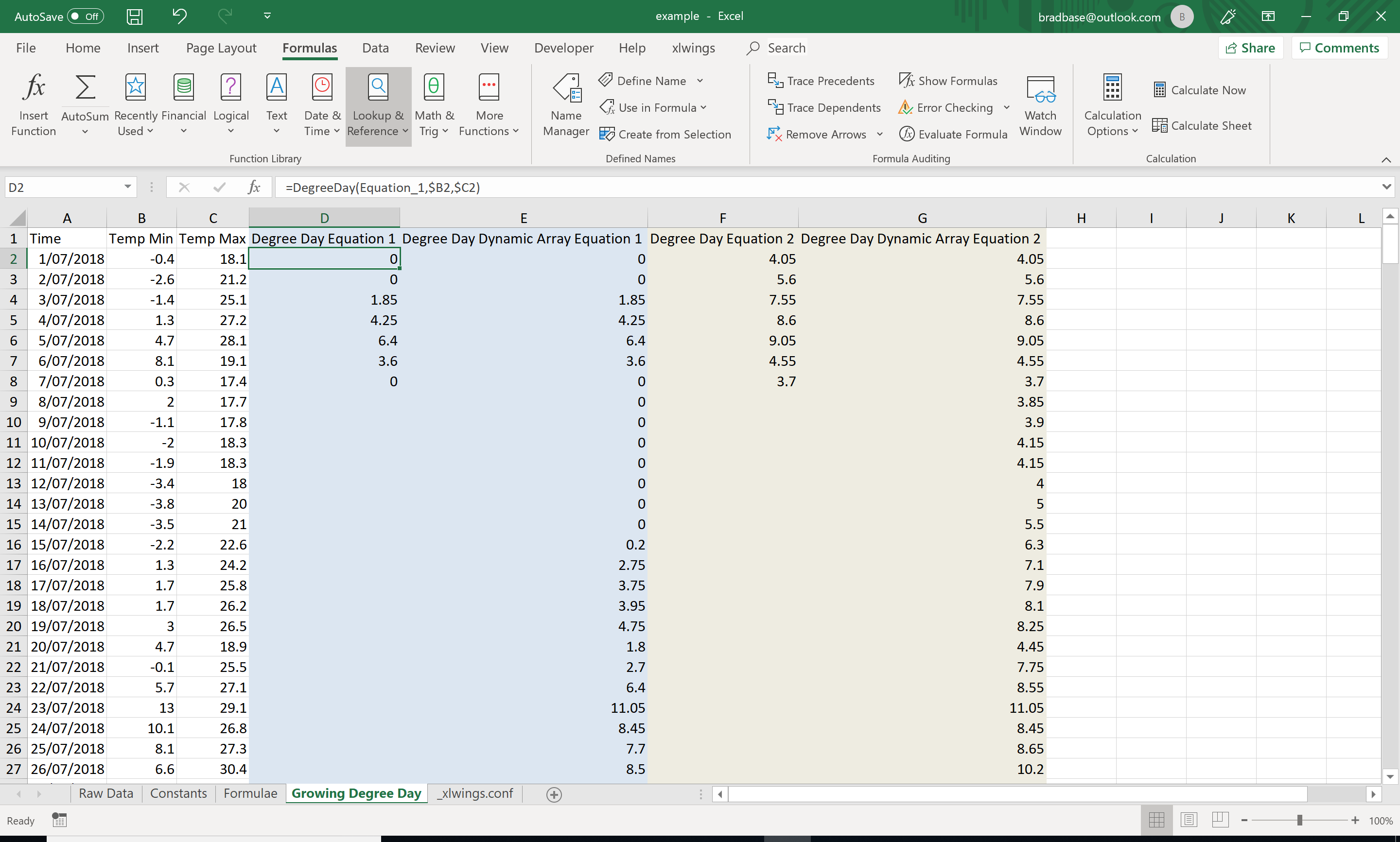

And so we can see the workings;

In the above example when DegreeDay first gets called it will;

- start a UDF server which has a Python interpreter

- load Equation_1 as a model in the FlyingKoala cache while specifying Equation_1 as the output cell and T_min and T_max cells as input

- apply values in $B2 and $C2 to T_min and T_max respectively

- run the Python code which actually calculates the ‘answer’/result

- return the result

For subsequent calls, which includes a workbook or worksheet re-calc, DegreeDay will;

- get Equation_1 from the FlyingKoala cache

- apply values in $B2 and $C2 to T_min and T_max respectively

- run the Python code which actually calculates the ‘answer’/result

- return the result

Obviously, a fill-down will change the row index like it would in any Excel formula…

=DegreeDay(Equation_1, $B2, $C2)=DegreeDay(Equation_1, $B3, $C3)=DegreeDay(Equation_1, $B4, $C4)…

That’s great for Equation 1. But what about Equation_2..? That’s easy – Still with the Fill-down approach;

=DegreeDay(model_name, T_min, T_max)

can now become something like

=DegreeDay(Equation_2, $B2, $C2)

The fill-down approach is awesome. But as you try and do larger and larger time series it becomes quite cumbersome. Each filled cell calculation needs to do a full round-trip from Excel to Python, get evaluated, and return a result from Python to Excel. All the data conversion in that takes time.

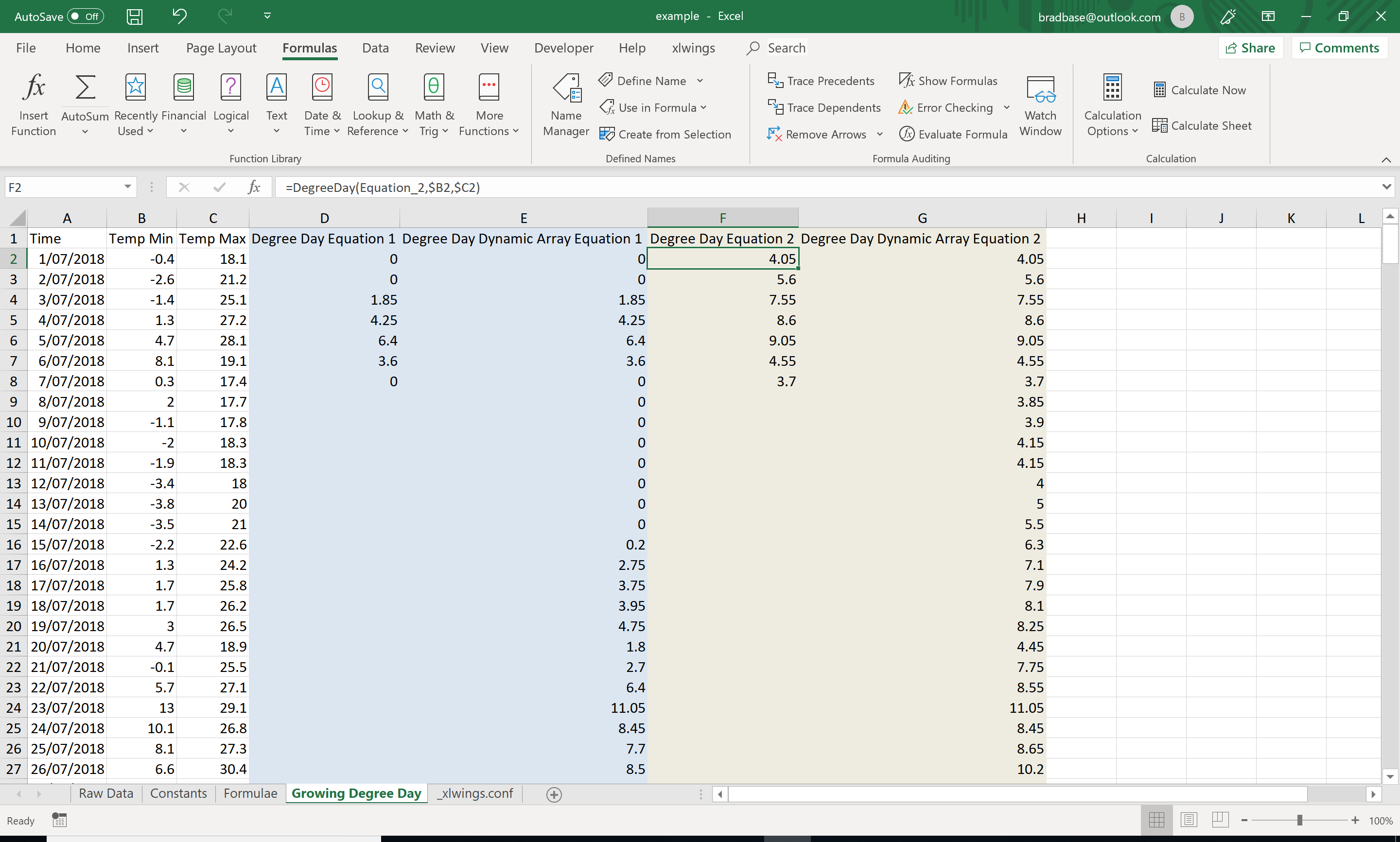

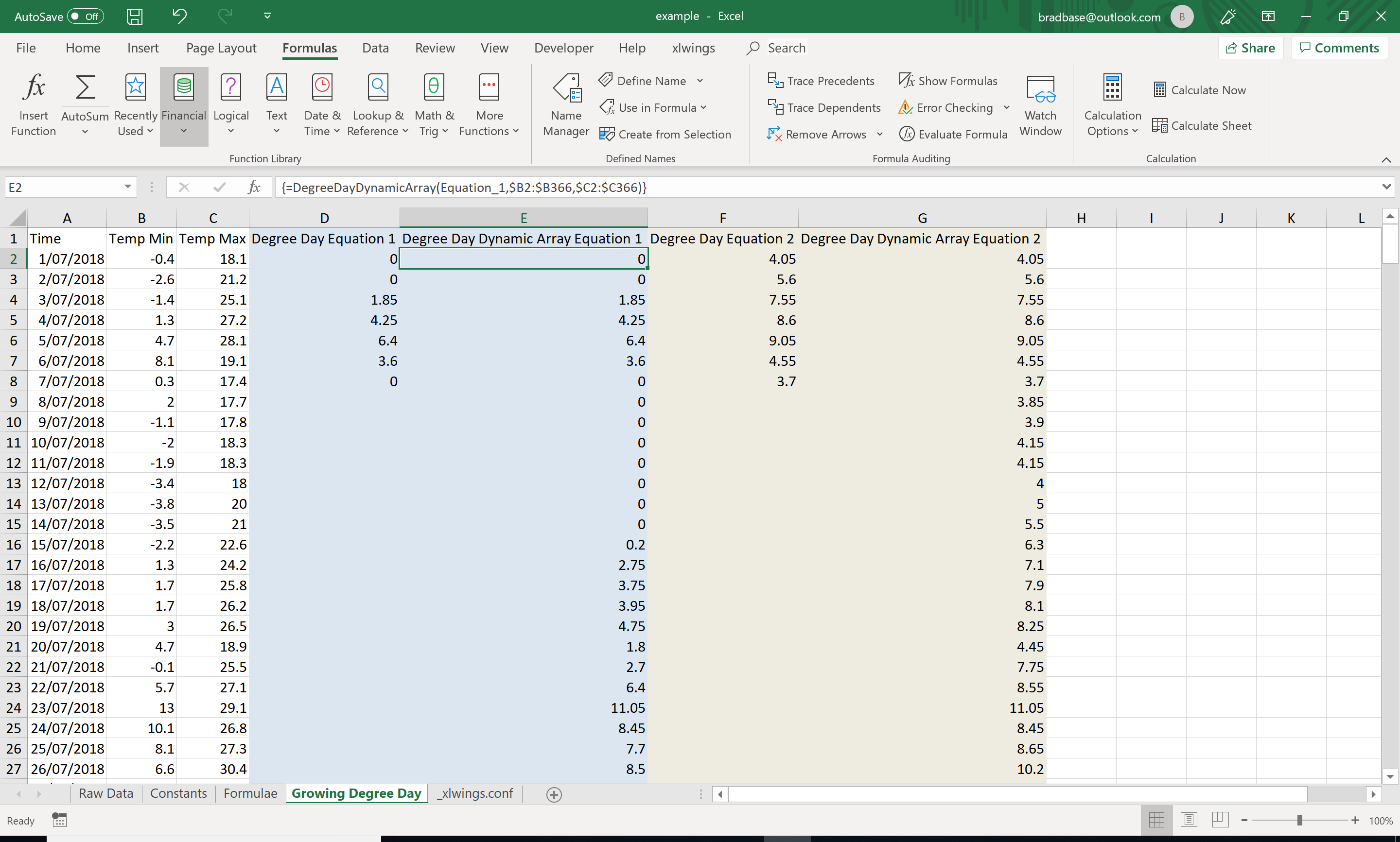

The solution to this round-trip per time period in the time series is to do the calculation ‘in bulk’. Send a range of cells for T_min and T_max, run the calculations on the array(/s) and send a resulting range back. Enter the Dynamic Array.

Dynamic Arrays are part of Excel but are going to help us a great deal when it comes to optimizing series calculation.

For the Dynamic Array approach

=DegreeDayDynamicArray(model_name, T_min, T_max)

can now become something like

=DegreeDayDynamicArray(Equation_1, $B2:$B366, $C2:$C366)

The ranges for T_min and T_max must be the same shape. eg; they need to have the same number of elements else you’ll get an error. They don’t need to be ranges next to each other. Knowing this, the below can be understood as a valid expression;

=DegreeDayDynamicArray(Equation_1, $B2:$B366, $E2:$E366)

Although I have no idea why this would be wanted, it is valid;

=DegreeDayDynamicArray(Equation_1, $B2:$B366, $G5:$G369)

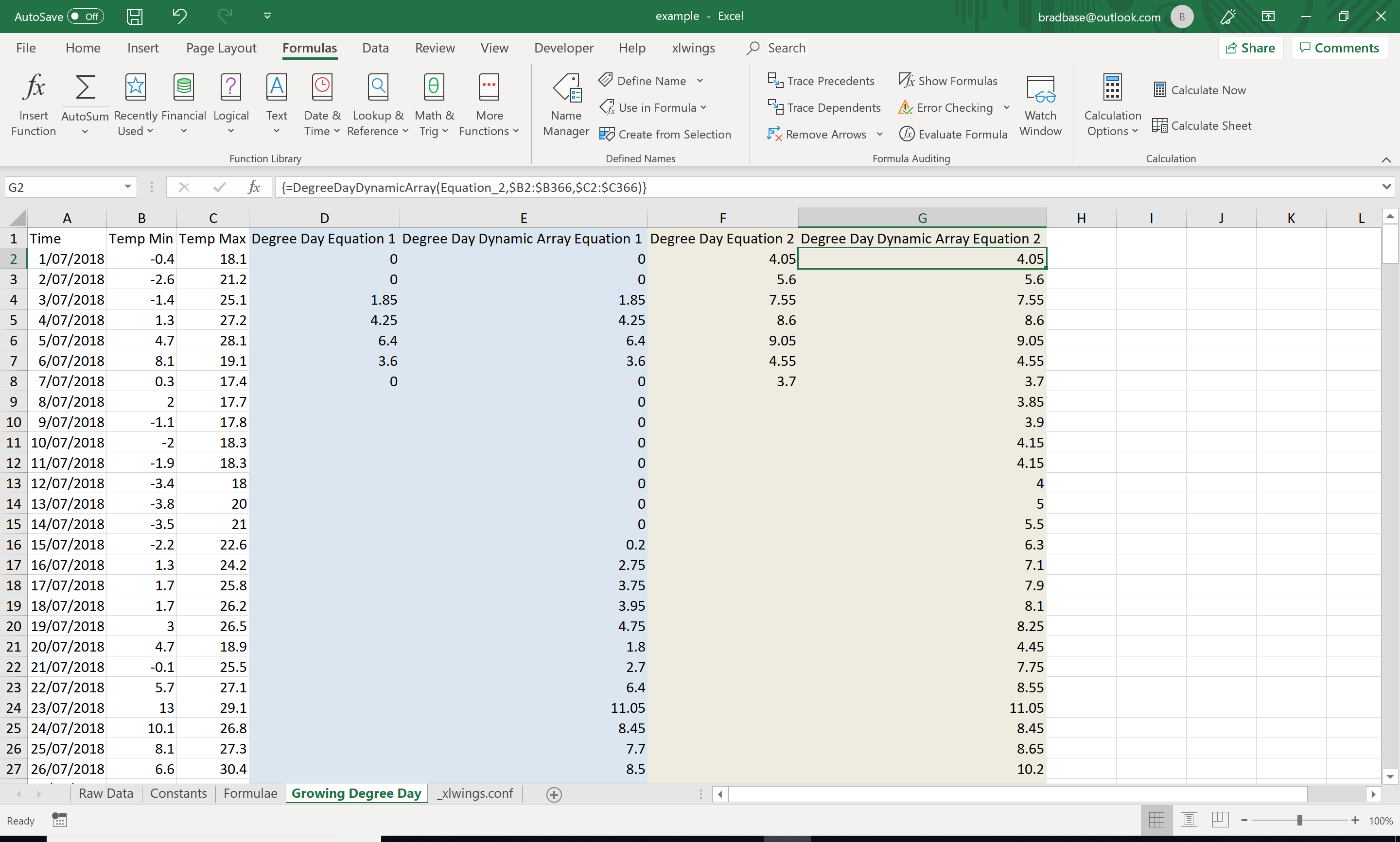

And so we can see the workings for the vanilla case Equation_1;

And for Equation_2

There is one more feature of these UDFs which is quite valuable and it stems from the fact that the model_name argument in either DegreeDay or DegreeDayDynamicArray is a range.

It can be defined as a variable.

To take the vanilla example for Equation_1 above;

=DegreeDayDynamicArray(Equation_1, $B2:$B366, $C2:$C366)

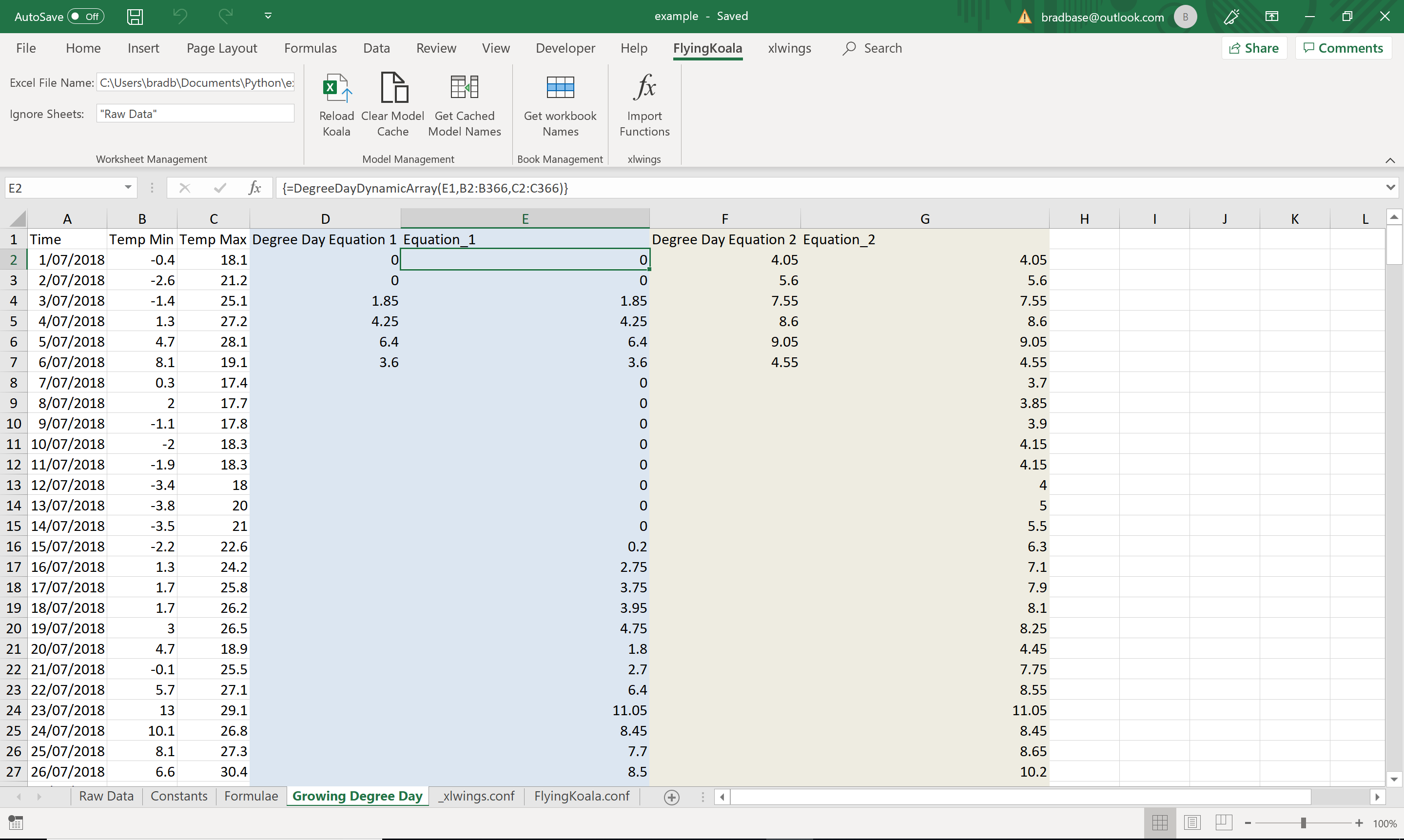

may become

=DegreeDayDynamicArray($E$1, $B2:$B366, $C2:$C366)

which defines the name of the column as the model name which the column is using.

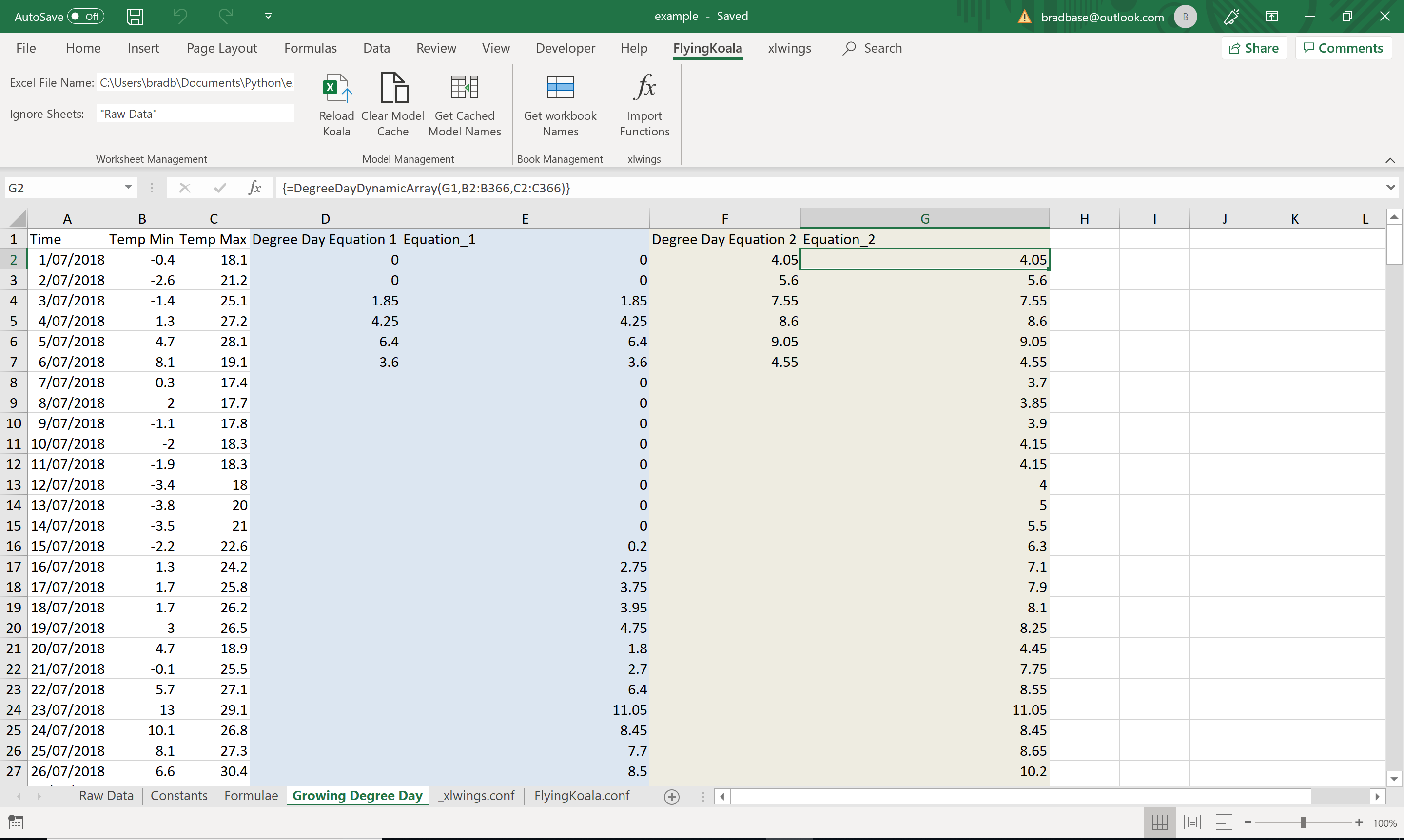

And, of course, same for Equation_2

=DegreeDayDynamicArray(Equation_2, $B2:$B366, $C2:$C366)

may become

=DegreeDayDynamicArray($G$1, $B2:$B366, $C2:$C366)

It is also valid to define yet another named range

=DegreeDayDynamicArray(active_degree_day_model, $B2:$B366, $C2:$C366)

Where active_degree_day_model is a named range somewhere in the workbook, maybe on a user editable worksheet formulating your assumptions.